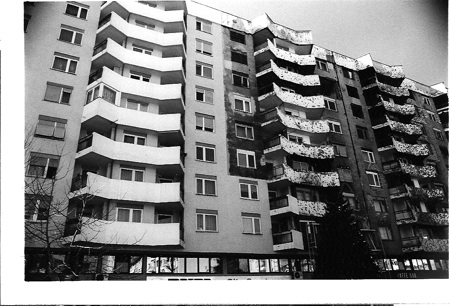

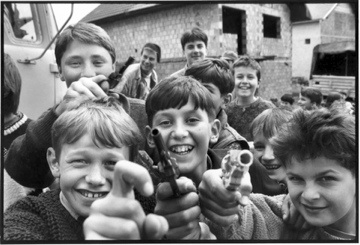

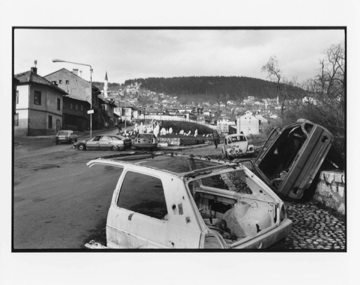

In 1993 Bill Carter was an aid-worker and documentary film maker living in Sarajevo, a city under siege from 18,000 Serbian troops firing artillery and mortar from the surrounding hills - and penetrated from within by snipers. Even though it was cut off from the rest of the world Carter saw the city as a sign of hope in the Balkan war because 'Sarajevans refused to be divided along ethnic lines with many Serbs joining the defence of the city against the Serb nationalist besiegers.'

It was when he met up with U2 on the ZOO TV Tour in 1993 that a plan came together to show young people in the rest of Europe what life was like in a besieged city on their continent. Four years later, with the siege over, U2 took the POPMART Tour to Sarajevo and next week they return to the region, with two shows at the Stadium Maksimir in Zagreb.

Bill directed the documentary

Miss Sarajevo (produced by Bono) and captured the whole story in a highly praised memoir 'Fools Rush In'. In April he was made an 'honorary citizen of Sarajevo' for being 'guided by the noblest principles, (which) enabled spreading of truth about Sarajevo and its citizens during the siege.' We invited Bill to recall the story of his friendship with U2 for U2.com and the story of the band's friendship with the people of the Balkans.

------------------

'In June 1993 I was in a television station when I overheard Bono and Edge speaking on MTV. They were addressing the issue of a united Europe, saying it was a dream worth dreaming. Of course I agreed, but there was only one problem: I was watching the TV being powered by a generator, surrounded by people emaciated to the point of looking like death camp survivors, and by the end of the month hundreds of people would die as snipers picked people off like cans lined up on a fallen log. I was standing in Sarajevo, ground zero of the most violent and bloody war in Europe since World War II. At that moment the idea of a united Europe seemed like a hollow pipe dream.

I had come to Sarajevo - a certifiable hellhole in 1993 - to deliver humanitarian food with a convoy of young men dressed as clowns. It was surreal but it worked. That day, after listening to U2 speak on MTV, I got the idea to reach out to the band. So, I forged some documents, called in a few favors and two weeks later I was sitting backstage in Verona hoping to get U2, the most powerful band in the world to do something. What? I really had no idea, but something had to be better than nothing.

That night I found myself face to face with Bono and Edge, partners in dreaming on very large scales. I told them stories of people I knew in Sarajevo. I told them about the musicians, about the full orchestra that gathered in basements to play their music. I spoke of theater productions, of painters who found a way to barter for their paints, and the cello player who plays to the dead in the cemetery after dark, his music echoing through a city of 250,000 souls, without food, water, gas, or electricity. By the end of the night Bono suggested he would come to Sarajevo in the next couple of days. I explained that, although it sounded like a great idea, it was impossible. The Serbian army that occupied the hills above Sarajevo kept close watch on the city and any gathering of people became an automatic target for an artillery attack. Disappointed, Bono, along with Edge, asked me to think of something. It was obvious they had no intention of giving up. They left me this thought: 'Think of something and we'll do it. It is time to do something radical.'

Thus the idea of the satellite link-ups was born. It was a simple solution. Instead of bringing U2 to Sarajevo we would bring Sarajevo to U2, and its stadium-filled audiences. During the satellite transmission in the Copenhagen show, a man from Sarajevo spoke into the camera and asked U2 if they would one day come to Sarajevo and play a concert. Bono replied, 'Yes, we will.'

In 1997, two years after the end of the fighting, U2 came to Kosovo Stadium in Sarajevo to play that promised show. To this day I'm not sure U2 knows the full influence this particular concert would have on the city, the country, or the region. To have 40,000 people gathered together in Sarajevo, from all over the Balkans, only two years after a violent war, had a profound effect on people. For some there was a deep-seated fear they would be standing next to a sniper who may have shot at them a few years ago. For others the fear was not in recognizing the enemy, it was the opposite: that they would not know if they were standing next to that person. How could they? The killers and victims look alike; they speak alike, and eat the same food. They are neighbors. But that night, once the music began, no one cared about last names, nations, or religion. All they cared about was the music. The simple celebration of music became a celebration of the end of the war. And the concert was unanimously perceived as a reward for those that survived.

By fulfilling their promise to play Sarajevo in 1997 U2 managed to do something that is more difficult than it seems: they literally extended a feeling of trust, they brought a sense of hope to Bosnians. Hope that this war was over. Hope that a sense of normality, manifested in the biggest rock band in the world, would return to Sarajevo. This feeling of hope and trust with U2 is spoken of often in the streets of Sarajevo. What is not talked about much is what Sarajevo did for U2. It was risky for the band to speak about war - to show the face of war on 80-foot screens, to make their audience squirm in a very uncomfortable situation. But it worked. They took a lot of flack for the satellite link-ups from Sarajevo into their ZOO TV shows but as Larry once told me, 'I think history will show that these satellites were a very good thing.'

As for the concert, the band has said that the concert in Sarajevo was one of the most memorable in their lives. But I also suspect the concert and the satellite link-ups gave the members of U2 a sense of hope as well. By seeing all these people who were once at war with each other gathered to dance, to sing, to express joy gave the band an affirmation that music, at least while the song is playing, can transcend borders, language, war, and nationalism.

It is easy to dismiss the actions of a rock band as frivolous or at least less important than the words and actions of politicians gathered in secret rooms. But U2's role should not be played down - by the simple act of getting involved, of doing something, they challenged the notion of a united Europe. I remember a NATO General at the Sarajevo concert telling me that there were 4,000 troops in the city to provide security but 'this band spends their own money and 40,000 people come together. We are in the wrong business.'

Today, almost fifteen years since the end of the war, peace in the Balkans is shaky. No one quite trusts it, but still it plods along, like a tireless train going uphill. It is a peace that relies on the trust of those that were enemies not long ago. No one thinks war will break out, but tensions are always brewing under the surface. Still, tourism is rebounding and industry is on the rise. These people are survivors. And on August 9th and 10th Makimir stadium in Zagreb will fill up with people from all over the Balkans to see the new incarnation of a U2 show. No one thinks that one rock concert can change the world, but for many U2's return signals something else: another chapter in a relationship started between the band and the region in the summer of 1993. And just like 1997 in Sarajevo, for one night 40,000 people will remember they are just people, with souls light enough to be lifted by the power of music.

Writer, photographer (he took the photos above) and filmmaker Bill Carter's most recent book is Red Summer. Find out more about what Bill is up to here.

PS Stadium in Zagreb, Maksimir, on croatian means Maksi=Maxi + Mir=Peace

Looking forward to see show, after long 12 years....

Hello from Zagreb...